Filichia Features: The Who's Tommy: See It. Hear It.

Filichia Features: The Who's Tommy: See It. Hear It.

This weekend, The Who's Tommy is enjoying yet another permutation at the White Plains Performing Arts Center.

This weekend, The Who's Tommy is enjoying yet another permutation at the White Plains Performing Arts Center.

Producing artistic director Jeremy Quinn is giving the 1993 musical hit one of his theater’s “Spotlight Productions.” These are mountings in which the metaphorical spotlight centers on one aspect of the show.

Here in this converted movie theater in a shopping mall, the spotlight shines on the seven-piece band that plays the score by Pete Townshend (with a little help from his friends John Entwistle, Keith Moon and Sonny Boy Williamson). Right from the start, musical director Kurt Kelley gets the juice from one of the greatest overtures of all time. Can you think of another that sounds as majestic?

Stressing the music is a good approach for those who have been considering The Who's Tommy but fear the expense. How can it be saved? Use director-choreographer Greg Baccarini’s concept and you’ll need only a couch, mirror, door frame, bed, a multi-purpose brick cube and, of course, a pinball machine. (Hmmm, is one of those available in this era when video-games dominate?)

Stressing the music is a good approach for those who have been considering The Who's Tommy but fear the expense. How can it be saved? Use director-choreographer Greg Baccarini’s concept and you’ll need only a couch, mirror, door frame, bed, a multi-purpose brick cube and, of course, a pinball machine. (Hmmm, is one of those available in this era when video-games dominate?)

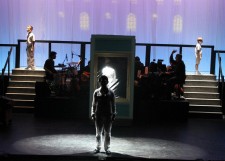

Baccarini puts the musicians on stage with a staircase at each side to allow for actors’ easy entrances and exits. Positioning a band center stage also aids a production in another way: it forces a director to push the action forward. Audiences have a better time when the action is positioned near the lip of the stage. Directors, don’t make theatergoers suffer like Tommy. Let them see it. Hear it.

Letting an audience know a show’s time frame without its having to search through a program in the dark is always a good idea. Baccarini knows this, and has the year in which each scene takes place projected on the backdrop, starting with 1940. But even if Baccarini didn’t add this, we’d approximately know, for he has Rosie the Riveter crossing the stage before some cast members dance the jitterbug.

Baccarini also has Army trainees to do pushups and calisthenics in time to the music. It’s an effective stage picture, so if this idea appeals to you, make sure at your auditions that you test all potential ensemble members and see if they’re up to such rigors.

However, Baccarini didn’t replicate a marvelous moment from the 1993 original stage production, possibly because he didn’t know about it, possibly because of the limitations of the stage on which he was working. On Broadway, during the opening scene, Captain Walker was to parachute from a plane. He was far upstage when he simply jumped into an open trap door and disappeared. How the audience oooohed in surprise and shock. This was especially noteworthy in 1993, which was still part of the era of barricades, falling chandeliers and helicopters; thus, to see such a simple and inexpensive effect get such a reaction showed that true stage magic can be provided by sheer imagination and doesn’t need a small fortune to succeed.

However, Baccarini didn’t replicate a marvelous moment from the 1993 original stage production, possibly because he didn’t know about it, possibly because of the limitations of the stage on which he was working. On Broadway, during the opening scene, Captain Walker was to parachute from a plane. He was far upstage when he simply jumped into an open trap door and disappeared. How the audience oooohed in surprise and shock. This was especially noteworthy in 1993, which was still part of the era of barricades, falling chandeliers and helicopters; thus, to see such a simple and inexpensive effect get such a reaction showed that true stage magic can be provided by sheer imagination and doesn’t need a small fortune to succeed.

Baccarini serves as his own costume designer, too, and goes for the usual black-and-white palette that is often seen in concert presentations. That the bridesmaids wear black at the Walkers’ wedding may seem bizarre, but it does make for a fascinating if inadvertent commentary. Considering how the Walker marriage will soon work out, the color was ominously apt.

To be fair to Mrs. Walker, she had been told that her husband had most likely died in World War II, so her moving on with Lover (as he’s solely known) doesn’t seem adulterous. Still, their consorting together doesn’t provide the homecoming that the very much alive Captain Walker expects or desires when he walks into his old bedroom. Getting killed isn’t what Lover anticipated this evening, either.

At his trial, Captain Walker is judged not guilty (for reasons that aren’t at all explained). But he’s certainly guilty of causing great damage to his young son Tommy, who is so traumatized that he can no longer see, speak or hear. Yes, even before Sondheim wrote about “The children you destroy together” in Company and that “Children will listen” in Into the Woods, Tommy’s songwriters made both points in the way that the Walkers dealt with their young son. “You didn’t hear it, you didn’t see it,” they insist. But denial doesn’t always work, and while it does here, it goes into overdrive.

By the way, is there any better way to introduce a shy and stage-frightened young boy to performing than to have him play Four-Year Old Tommy or Ten-Year-Old Tommy? Each lad won’t be required to do anything but stand on stage expressionless and look fourth-wall. Over the run, each boy will become accustomed to having an audience in front of him; he’ll relax and see that there is nothing to fear. This will prepare both boys for the next step: singin’ and dancin’ in one of your subsequent productions.

If Tommy could speak, he’d certainly have a great deal to say about Uncle Ernie and Cousin Kevin. These are the seedy relatives entrusted to be the lad’s babysitter.

“Do you think it’s all right?” Mrs. Walker asks her husband. Here Megan Smith has a look of “Please say yes,” matched by the equally hopeful look that Matthew Curtis does. They make the point that The Who intended: some parents will leave their kid with anyone at all just to have a night out of the house and to be rid even temporarily of the responsibilities of a child.

Uncle Ernie, a child molester, proves himself to be the family’s blackest sheep. It’s a tough scene and at the performance I attended, it got no applause. Don’t be offended if your production gets none at this point, too. Audience members inherently feel that if they clap, they’re essentially endorsing the horrors of what they’ve just seen. When this performance of Tommy ended, I wondered if the parents who’d left their kids with babysitters immediately rushed across the street to Walmart to purchase a nanny-cam.

However, for “I Believe My Own Eyes” – in which the Walkers admit they’re discouraged – Baccarini purposely directs so that no applause is expected after it concludes. He may have feared that the audience wouldn’t respond to this “new” song that many don’t know; it wasn’t part of the original 1969 concept album that is one of the rock world’s most famous. I daresay that it would have got a nice hand, given how potently Curtis and Smith delivered it.

Cousin Kevin isn’t much better than Uncle Ernie; sadism is his game. And yet, there is a message of “No pain, no gain” here: Cousin Kevin does introduce Tommy to pinball, which turns around the lad’s life.

Cousin Kevin isn’t much better than Uncle Ernie; sadism is his game. And yet, there is a message of “No pain, no gain” here: Cousin Kevin does introduce Tommy to pinball, which turns around the lad’s life.

Here Cousin Kevin and Uncle Ernie lift and carry Tommy around the stage, which effectively conveys the boy’s helplessness. Once again, at auditions, make certain that each of your contenders will be able to give the kid a lift.

The Walkers hope that leaving Tommy with a Gypsy might provide a new type of therapy. Here the Gypsy is solidly played by Elizabeth Pryce Davies, who doesn’t have mere acid in her veins when singing “Acid Queen,” but the fluid with which DieHard Batteries are filled. It’s such a great cameo for a full-throated and fearless actress.

And what’s the best aspect of The Who's Tommy, be in it full production or concert? The musical suggests that no matter how unhappy someone may be, there is something that will make him discard his misery and unleash his passion. It’s happened for so many through musical theater; who knows how many more will come to love the medium through this White Plains Performing Arts Center presentation or beyond?

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His upcoming book, Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks – a Very Opinionated History of the Broadway Musicals That Did Not Win the Tony Awards is now available through pre-order at www.amazon.com.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His upcoming book, Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks – a Very Opinionated History of the Broadway Musicals That Did Not Win the Tony Awards is now available through pre-order at www.amazon.com.