Filichia Features: New Ideas for Les Miserables

Filichia Features: New Ideas for Les Miserables

Have you ever seen a production of Les Miserables in which "Empty Chairs at Empty Tables" had full chairs and no tables at all?

Have you ever seen a production of Les Miserables in which "Empty Chairs at Empty Tables" had full chairs and no tables at all?

Leave it to Aubrey Berg, the chair of the musical theater department at the University of Cincinnati-Conservatory of Music. In his two-decades plus at the school, he's thought out of the proverbial box so routinely that he seemingly doesn't allow for the possibility of a box.

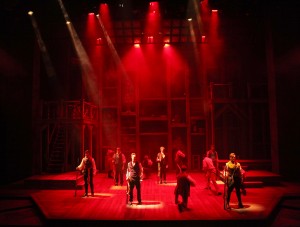

Let's start a few scenes earlier. Enjolras, Marius and the other revolutionaries are fighting what will be their final battle against the establishment forces. In many a past production of LES MIZ, as we've chummily come to call it, the students have their backs to us. shoot upstage for a while and then fall onto the stage. Fine; that's a time-honored way of handling a battle.

Is it the most powerful way? Not any longer. Berg still has his soldiers face upstage and firing but then, one by one, each student spins around, slams his rifle butt against the floor, stands tall but rigid with an expressionless face, as his entire body is framed in in a pool of sympathetic light. He has been killed, and our seeing the immobile faces of genuinely young men -- none of the Cincinnati kids is older than 22 -- who play these characters makes a greater impression.

During the blackout, they all scurry off, leaving the empty stage for the townswomen, all of whom are dressed in mourning clothes. It's true, isn't it, that some of these women would have become at least a little fond of these men who had readied them for battle. Now that these young men are no more, these women could conceivably become sentimental about them. The chairs they bring on could be for a memorial service they are about to hold. "Turning," they sing as usual, and indeed they turn before leaving the chairs and walking off mournfully.

And that's when Berg has the dead soldiers return and sit in these chairs as an infirm Marius sings "Empty Chairs at Empty Tables." There's an added poignancy when he sings "All my friends are dead and gone," for while they are there, their same stone-faced, blank-expressionless faces tell us that they are not. What we're seeing is Marius' memories of their faces when he saw them killed or at least imagined them dead.

"My friends, forgive me," he implores. But they do not because they cannot. Marius gets up, grabs his cane, limps around, goes to many of them and looks each in the eye. None of this matters. One by one, each arises, picks up his chair and takes it with him; none will again be seen until the curtain call.

One character is not filling a chair. Berg positioned his little Gavroche on the floor, sitting with pulled-up knees that he clasps with his arms. Berg uses two different young actors in the roles, but he manages to get each of them to look far older than his years. The cockiness is long-gone.

One character is not filling a chair. Berg positioned his little Gavroche on the floor, sitting with pulled-up knees that he clasps with his arms. Berg uses two different young actors in the roles, but he manages to get each of them to look far older than his years. The cockiness is long-gone.

Gavroche dies far more dramatically in Berg's production. far more dramatic. Only those with eyes that an eagle would envy would notice, in the midst of bisque-thick fog, the shadow of a soldier taking a shot at the lad. The military man is easier to see as he moves closer for the second shot. But what makes this sequence so chilling is that the soldier then moves closer, only a foot or so away, and stands directly behind the wounded kid.. He pauses, takes his aim and takes his time to ensure that he won't miss and that he will kill this defenseless little boy.

In many other Les Miz productions, the three shots that hit Gavroche are anonymous ones that come out of nowhere; they might well have been scattershot volleys whose shooters had hoped to maim or kill one foe, any foe. How much more frightful to witness a staunch soldier not care for a second that he's exterminating an unarmed child. The kid's the enemy, and that's all there is to that.

Bam!

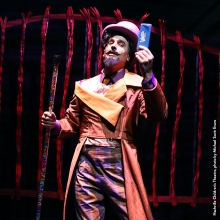

Berg also shows he can add a lighter if somewhat blackly humorous touch to "Master of the House." Into the Thenardiers' inn comes a blind customer, tapping his cane as he enters. In the middle of the song, Thenardier snatches the cane from the man, and almost -- almost -- makes it half of a hat-and-cane dance move. To have him go all full out would be overkill, and just when you assume and fear that Thenardier will go over the top, he loses interest in the cane, tosses it to an employee and continues the number without it.

Meanwhile Madame Thenardier is removing the blind man's back pocket handkerchief. These two will steal anything, whether or not they want it or have a use for it; for them, it's all about the game of comimg out ahead.

The set? You can turn the stage upside down while searching for the show's trademark turntable, but you won't find it. Instead, Berg ordered something that resembles a shadow box, one of those little mini-cabinets that hangs on walls in lieu of a painting – you know, they type that sports tiny shelves that encase miniature warrens; in each, a piece of bric-a-brac is displayed. Scenic designer Mark Halpin obliged nicely, and Berg uses virtually the entire expanse as his barricade.

More interesting still: in the scene leading into "Red and Black," two revolutionaries are seated a table, seemingly playing with books. No; what these men are doing is designing and planning the barricade.

That's Berg's sense of detail for you: his ensemble is never mere window dressing, for each actor is required to invent a full-bodied, self-actualized person who knows where he's been, where he is now and, more often than not, has at least an idea of where he's going.

That's Berg's sense of detail for you: his ensemble is never mere window dressing, for each actor is required to invent a full-bodied, self-actualized person who knows where he's been, where he is now and, more often than not, has at least an idea of where he's going.

That principle applies to the principals, too. So how apt that when the older Eponine approaches Marius, she gives him a friendly punch on the arm as a way of saying hello. After all, he treats her as a good buddy, so she'll maintain that tone for their relationship.

What Eponine is hoping, of course, is that if she meets Marius on his terms, stays friendly and doesn't make a fuss, he'll let her stay in his life. That will allow her to bide her time until the wonderful moment when the guy finally wakes up and says, "My God! How could I have been so blind! It's Eponine whom I really love!"

Until that marvelous day -- which we know will never come -- Eponine feels her best course of action is to give Marius that we're-just-good-friends punch on the shoulder. How smart of Berg to --

But wait! When I talk to the students after the show, I learn that this idea was the brainchild of Lawson Young, who plays Eponine. All right, so Berg can't think of everything. But he comes mighty close, and may well have given you some gourmet-level food for thought on how you can stage your upcoming production of Les Miserables.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His new book, Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks – a Very Opinionated History of the Broadway Musicals That Did Not Win the Tony Award is now available at www.amazon.com.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His new book, Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks – a Very Opinionated History of the Broadway Musicals That Did Not Win the Tony Award is now available at www.amazon.com.