The MTI office will close at 1 PM ET on Friday, May 23rd and remain closed through Monday, May 26th in observance of Memorial Day. Office operations will resume on Tuesday, May 27th.

Filichia Features: Shirley Jones and Patrick Cassidy Discuss The Music Man

Filichia Features: Shirley Jones and Patrick Cassidy Discuss The Music Man

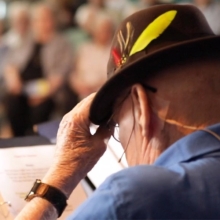

Shirley Jones as Mrs. Paroo and son Patrick Cassidy as Harold Hill in a 50th anniversary production of "The Music Man" at the Bushnell Theatre in Hartford, Ct. (Ben Gancsos)

Shirley Jones as Mrs. Paroo and son Patrick Cassidy as Harold Hill in a 50th anniversary production of "The Music Man" at the Bushnell Theatre in Hartford, Ct. (Ben Gancsos)

It all started from a casual, off-the-cuff story.

“About a half-dozen years ago,” says Patrick Cassidy, “I was Harold Hill and Mom was Mrs. Paroo in a full production of The Music Man at the Bushnell in Hartford.”

“Mom,” not so incidentally, is Shirley Jones, who has a history with The Music Man. She was, of course, Marian the Librarian in the 1962 Oscar-nominated Best Picture.

“During a rehearsal,” continues Cassidy, “we shared a story with our director, Phil McKinley who got excited and said, ‘Let’s tell that at the end of the show!’ We did, and it really went over. When my brother Shaun suggested that we do a MUSIC MAN concert with a symphony orchestra, we did with Marvin Hamlisch in Pittsburgh and Kansas City – and once again, we told the story.”

And once again, it was a warmly received part of the show. That spurred Cassidy to consider an evening in which Shirley Jones could share many stories of the filming of The Music Man interspersed with many songs from the show itself while many photographs of the filming could be projected on a large upstage screen.

“I went into my hotel room and started writing down some ideas,” he says. “I felt like Kate Winslet in Titanic.”

In 2012, while Glenn Casale was directing the two in a Sacramento production, he had an inspired idea. Jones would come on stage in spotlight and watch Brandi Burkhardt as Marian the Librarian sing “Goodnight, My Someone” and “My White Knight.” Her expression alone would show how she fondly remembered this important component of her illustrious career.

All these ideas have forged together so that Cassidy and Jones could do a tour of The Music Man In Concert. Best of all, they’d debut it in no less than Mason City, Iowa -- the real “River City” that Meredith Willson had immortalized in his 1957-58 Tony-winning musical.

A chat with the two shows that Mother and Son had different aspirations while growing up. “I desperately wanted to be a veterinarian,” Jones asserts. “I loved every animal from birds to skunks. My parents were the ones who thought I should go into show business.” She smiles warmly. “Isn’t that a very different story from what you usually hear?”

Although Jones had been singing with her church choir in Smithton, Pennsylvania since the age of six, her parents’ aspirations didn’t become cemented until she was 12.

“A camp counselor said, ‘Don’t you know what you have here?’” says Jones, still sounding a bit mystified at this early rave review.

So she spent her summers at the Pittsburgh Playhouse while filling fall, winter and spring musing about the day she’d be curing animals’ ills. A few days each summer, however, were reserved for a family trip to New York City. “Mom would go shopping and dad and I would go to a baseball game or a Broadway show,” she recalls.

Fine – but in 1953 when Jones was 19, what made her call a pianist friend when she arrived in Manhattan? If the ivory he played had still been on live elephants, then the veterinarian-to-be would have had sufficient motivation. But those 88 pieces on the piano keyboard hadn’t been part of any elephants in years.

Freud maintained that there was no such thing as an accident, didn’t he? Whatever the case, the pianist told Jones that Rodgers and Hammerstein were holding open auditions, so she should show up and be seen. “I said no, but he talked me into it,” she says.

Or was Jones purposely moving away from one type of menagerie to another: the theater? After all, Jones reports that there was a l-o-n-g line of people to be seen, and she could have taken one look at her competition and said “Forget it.”

But she stayed. When her turn finally came, the casting director asked “What have you done?” to which she unabashedly said “Nothing.” But then Jones showed him something. “After I sang,” she says, “he went across the street to City Center where Mr. Rodgers was rehearsing an orchestra. He came over and heard me. Mr. Rodgers asked if I could wait 20 minutes until Oscar Hammerstein could get there.”

Jones’ pianist friend hadn’t bargained for this; he had to catch a plane and left. “We’ll think of something,” Rodgers told her – and did when Hammerstein arrived. They took her across the street where she sang selections from Oklahoma! with that august orchestra. R&H offered her a contract on the spot; three weeks later she was a South Pacific nurse and soon they brought her into their new musical Me and Juliet.

There went those veterinary dreams – although she would encounter a wolf in Richard Rodgers. “He called me to his office and I sat down just as I saw him locking the door,” she says. “Uh-oh! I’d already heard that he liked blonde chorus girls. He didn’t put his arm around me, but he put it around the chair and asked ‘Do you have a boyfriend?’ I told him I was engaged, which I wasn’t. And then I said, ‘You’re just like a father to me’ and his face fell.”

(To any young performer out there who encounters the same lamentable situation, remember to play the “Father” card. You’ll probably short-circuit any additional problem.)

As for Patrick Cassidy, he became entranced with show business at an early age. “When I was four and my father (Jack Cassidy) did (‘It’s a Bird … It’s a Plane … It’s) Superman,’ I remember sitting on Bob Holiday’s knee,” he says, citing the actor who was portraying The Man of Steel.

There were plenty of kids in Jones and Jack Cassidy’s 1968 musical Maggie Flynn, but their son wasn’t right for any of them; the show required African-American moppets -- and non-traditional casting hadn’t quite started. “At least I got to play with them backstage,” Cassidy says.

Jones wouldn’t have wanted him in the show, anyway. “I discouraged all my children from show business,” she says without sounding the slightest bit apologetic. “Doctor! Lawyer! That’s what I wanted for them. Much easier.”

“What really rankled me is that Mom didn’t get me on The Partridge Family,” Cassidy says, referring to the 1970-74 hit series in which Jones played the mother of a touring musical brood. “Jeremy Gelbwaks and then Brian Forster played drums on the series. Well, I could play drums! That those boys were around my age made it harder for me to take. Mom just wouldn’t let me. ‘You’re going to school’ she demanded.”

Those who remember the series and recall that David Cassidy appeared on it may wonder why Jones didn’t nix his participation. Simple: David’s mother was Evelyn Ward, Jack Cassidy’s first wife. Jones had no particular jurisdiction over him as she did her natural-born son from Cassidy.

But a mother can only fight a child for so long. When Jones was hired to play Maria in a tour of The Sound of Music , she allowed 15-year-old Patrick to play a role for which he was two years too young: Rolf, the lad who’s seventeen going on eighteen. (Not so incidentally, Sarah Jessica Parker and a few of her siblings portrayed some of the von Trapp kids.)

“When I saw what he could do in Sound of Music,” Jones says with a definitive nod, “I knew Patrick was talented.”

“To tell the truth,” he says, “I was terrible.”

“No, he wasn’t!” Jones quickly states. Whether this was a performance that only a mother could love is a question that can never be convincingly answered for the rest of us.

As much as he wanted to perform, Patrick was even more interested in football. “When I was quarterbacking for Beverly Hills High School in my senior year,” he says, “I was actually leading the nation’s high schools in passing. Many colleges, including Stanford, had their eye on me – until I broke my collarbone.”

Strong collarbones are not as required in theater. “I’ve always felt that sports is a form of entertainment,” Cassidy says. “Throwing a touchdown pass in the fourth quarter to win the game is the same as singing and nailing an eleven o’clock number.”

(He’s right, Would that more people would realize the affinity between sports and the stage. When you think about it, both baseball and musicals have runs and hits, don’t they?)

Cassidy was assuaged when he heard that the drama club was doing THE MUSIC MAN. “With my mother having done the movie, I thought I was a shoo-in for Harold Hill. Better still, Mom was friendly with Dick Van Dyke, who was touring in the show at the time. He actually taught me ‘(Ya Got) Trouble.’ And then,” he says, pausing for dramatic effect, “I got cast as Salesman Number Five. Steve Lawrence and Eydie Gorme’s son was chosen as Harold Hill.”

The moral of the story, as many of you have already learned from bitter experience, is to never assume you have a part. You may think you have it in the bag, but a director can very easily poke a hole in that bag.

No question that Patrick Cassidy would now get the part of Harold Hill, however – and that he and his mother would get to tell that story that inspired THE MUSIC MAN IN CONCERT. Oh, and what was that story? That’s for next Friday, friends.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His new book, Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks – a Very Opinionated History of the Broadway Musicals That Did Not Win the Tony Award is now available at www.amazon.com.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His new book, Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks – a Very Opinionated History of the Broadway Musicals That Did Not Win the Tony Award is now available at www.amazon.com.