Filichia Features: The Baker's Wife is Cookin'

Filichia Features: The Baker's Wife is Cookin'

Here’s the way to advertise it: “From the composer-lyricist of Wicked, Pippin and Godspell.”

Here’s the way to advertise it: “From the composer-lyricist of Wicked, Pippin and Godspell.”

That’s ad copy that’ll sell tickets – and you wouldn’t be lying.

Oh, your audience may think you’re fibbing once it begins to hear Stephen Schwartz’s score for The Baker's Wife. It’s clearly his most ambitious and it doesn’t remotely resemble any of his others. There isn’t a pop rock tune among any of the bakers’ dozen (okay, plus one) songs.

Because the musical takes place in the ‘30s in the south of France, Schwartz had to find an appropriately Gallic sound. Did he ever. Many musical theater savants consider this his best score.

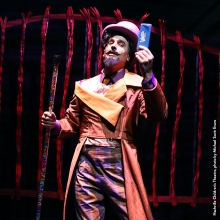

Kyle Fabel’s recent production at New York University had theatregoers sitting around a thrust stage; thus, we could see the others’ keenly interested eyes the moment their ears heard the opening number: “Chanson” must be among the most beautiful swirling waltzes ever written. Later, at both intermission and after the show, theatergoers were exclaiming to their seatmates “I love this music! I love this show!” Many an exclamation was matched with a hand over a heart, not to suggest “I swear it!” but to say “I’m so moved!” Thank, too, bookwriter Joseph Stein who adapted the 1938 film that Marcel Pagnol crafted from Jean Giono’s novella.

The audience learned that Amiable is a baker who arrives in a town so provincial that if Belle (of Disney's Beauty and the Beast fame) had moved here, she would have thought her former burg positively Parisian.

Amiable has brought with him his young wife Genevieve and their cat Pompom. Because he is much older than she, some townspeople think that he is her father. Many more predict that she’ll soon stray.

This isn’t on Amiable’s mind. In the charming romp “Merci, Madame,” he not only sings his joy to both her and Pompom, but does a few dance steps, too. If there’s truth in “You’re as young as you feel,” Amiable may be the youngest one on stage. (Yes, Sam Stone is an NYU student, but he was able to age himself into the role.)

Fabel made certain that Harriet Taylor, his Genevieve, enjoyed his enthusiasm and laughed affectionately. Taylor did, however, include the slightest subtext of embarrassment when she saw Amiable try so hard to convince her that he was still young.

Amiable says “I love you,” to which Genevieve says “I know you do.” In lesser shows, a husband wouldn’t notice that his wife didn’t say “I love you” in return but would assume that her response inherently included the sentiment. Stein instead has Amiable call her on it. No, he doesn’t make any more of it than that, but Amiable lets the audience see that he isn’t the average clueless husband.

What’s really on Genevieve’s mind? She reveals it in “Gifts of Love,” the best bolt-of-lightning ballad that too few people know. Genevieve tells in its verse that she’d been dumped by a man she once genuinely loved. We could infer that she married Amiable on the rebound and now, after making a lifetime commitment, she is starting to regret it.

On the scene comes handsome, virile and passionate twentysomething Dominique. He’s seduced all the pretty young women in town, and now he sees his newest candidate for conquest.

Give Genevieve credit because she tries so hard to resist Dominique. When he calls her by her first name, she bristles at his being overly-familiar and insists on “Madame” to remind him she’s married. Then she abruptly leaves to help Amiable make bread.

Their wares are so great that the townspeople joyously sing about “Bread!” The students did very well singing with their mouths full, but Fabel and choreographer Byron Easley had them over-emote the bread’s wonders. The number might have been more successful if each chorus member had adopted a different level of love for Amiable’s taste treats, from pleased to pleasantly surprised to wistfully appreciative to ecstatic.

Few playbills prominently display on its page of credits “And thank you to our bakers! Amy’s Bread: West Village. Le Pain Quotidien: Union Square & Mercer Street.” Yes, Fabel knew that he needed real bread and went out and got it. It’s a good reminder that whatever you show you do, you should entice merchants who deal in related fields or wares to give you the props you need. Program credit will be their reward.

As Dominique, Matthew Stoke had the right cock-of-the-walk mentality, even flirting with first-row patrons. However, Fabel ensured that he not become Gaston in the aforementioned Disney's Beauty and the Beast; that’s a cartoon, and The Baker's Wife is a more serious musical.

Dominique’s statement to Genevieve -- “If you were mine, I wouldn’t leave you alone for a second” -- is a very intoxicating compliment. One morning Amiable awakes to find her gone and if that isn’t enough, even Pompom has run away.

Amiable is so devastated that he stops baking. That mobilizes the town to find her and get her to return. There’s a stinging irony here: the citizens don’t have compassion for their fellow man; they just want to have that delicious bread every morning. If Amiable had been a lackluster baker, they’d have let him wallow in his own grief and never give him a second thought.

No, we can’t accuse The Baker's Wife of being sentimental. Remember, Stein also wrote the book to Fiddler On The Roof, where the town’s beggar asks a question that these Frenchmen could essentially rewrite: “If you have a bad marriage, why should we suffer?”

And yet, by show’s end, the townspeople come together. A disassociated group of citizens become an extended family of friends.

As for Genevieve and Dominique, their love affair, to cite a song of yore, is too hot not to cool down. Taylor’s Genevieve delivered Schwartz’s most perceptive eleven o’clock ballad: now that she’s lived day-to-day with Dominque and has seen his liabilities as well as his assets, she had to acknowledge that he has heat but “Where Is the Warmth?”

Warmth is what she’d received from Amiable – but there isn’t any when she arrives home -- at the same time that Pompom does. This allows Amiable to chastise the cat, NOT Genevieve, although he does it while his wife is watching: “So you’re back, you alley cat, you rotten thing. Tired of running around, you come back where it’s nice and safe, hah? You good-for-nothing. You don’t care who misses you, who loses sleep over you, do you? Where did you go, running after some tom cat, hah? What did he have that was so wonderful that you had to leave home? You stupid creature! Is that why you came home, Pompom, because you were cold and hungry. And will you leave again?”

To which Genevieve says, “She will not leave again.”

“For if you will leave again,” says Amiable, “do it now, for it would be less cruel.”

To which Genevieve again says, “She will not leave again.”

While there were some dry eyes in the house, there were plenty of wet ones. We liked that Amiable didn’t automatically forgive Genevieve; he would then be a man without enough self-worth. Amiable believed that he had a lot to offer – especially a great deal of love – and knew that any woman who shared his life would be a lucky one. There would have to be some new terms in any peace treaty he signed.

If you do The Baker's Wife, you’ll also need performers who can enact convincing French accents. (Fabel had them.) The show will be as unwelcome as a burnt baguette if your cast goes into the clichéd “haw-haw-haw” and “ze bay-kurr” mode for those in the many good supporting roles. Two men carry on a Hatfield-McCoy-like feud that is so many generations old that no one knows the initial cause. One husband is terribly tyrannical with his wife, always silencing her whenever she wants to express an opinion. She eventually tells him off. While in most musicals that’s enough for a husband to straighten out and plead for a reconciliation and a fresh start, here she still winds up leaving him. Many in the audience were ready to say “Merci, madame!” to her.

Of course you don’t need a dazzling-looking leading man, but he has to be able to sing superbly as must everyone else. Let’s put it this way: Genevieve was originally played by Patti LuPone. ‘Nuff said.

Costumes? Nothing fancy. Get those three-dollar housedresses from thrift shops. (Costuming nuns and priests may be a bit dicier.) The set can be simple, as designer Lauren Barber proved; she created a two-level structure with the oven on the first level and a bedroom above. The rest of the stage was empty, representing the town square.

Fabel’s other mistake in an otherwise stellar production involved Pompom. He didn’t use a genuine, alive-and-ambulatory cat, but a stuffed animal.

The care and feeding of a real animal that will also cooperate on stage isn’t easy. But considering that the show’s ending very much depends on the presence of a cat, a real one is a necessity.

All right, there IS a scene in which Pompom is stuck in a tree, and a real cat would have to be Method-trained to stay in place. Here an audience would forgive your using a faux chat. That, however, is the only time you should compromise.

Think about the scene in Annie when the policeman challenges Our Heroine to call that dog over to her so she can prove that that the stray is hers. Would we have the same feelings and go “Awwwwwww!” if Annie’s “C’mere, boy!” resulted in a stuffed or animatronic animal rolling across the stage? No, and we wouldn’t rejoice nearly as much at the final curtain if Annie opened that oversized present and a stuffed dog popped out of it.

Pompom is a far more important character than Sandy, so make certain that you get a real feline in real fur. (Hey -- is Gus the Theatre Cat still working?)

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His new book, Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks – a Very Opinionated History of the Broadway Musicals That Did Not Win the Tony Award is now available at www.amazon.com.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His new book, Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks – a Very Opinionated History of the Broadway Musicals That Did Not Win the Tony Award is now available at www.amazon.com.