Filichia Features: A Guide to Presenting A Gentleman’s Guide To Love & Murder

Filichia Features: A Guide to Presenting A Gentleman’s Guide To Love & Murder

A musical comedy about a serial killer?

Can theatergoers really be expected to laugh as they witness murder after murder? Isn't that a lot to ask of those who enjoy musical comedies?

And yet, A Gentleman's Guide To Love & Murder managed to have a two-year-plus Broadway run and win Best Musical in the 2013-2014 season Tony race.

How did the creators manage to pull this off? Just the idea of it sounds somewhere between crazy and impossible.

(And don't try to rebut with Sweeney Todd. I said musical comedy, remember?)

First, bookwriter Robert L. Freedman wisely retained the time and era of the musical's source material: Roy Horniman's 1907 novel Israel Rank: The Autobiography of a Criminal. We were transported to London more than a hundred years ago, where men wore ascots and waistcoats and women had bustles under their gowns.

Thus, theatergoers were distanced from the situation -- unless they hailed from England and were very old.

Freedman and his co-lyricist Steven Lutvak helped with their wry opening number "A Warning to the Audience." It began "For those of you of weaker constitution / For those of you who may be faint of heart / This is a tale of revenge and retribution / So if you're smart / Before we start / You'd best depart."

Coupled with composer Lutvak's jaunty music, we could see that the writers' tongues were so firmly planted in their cheeks that you'd think that they'd had entire Tootsie Roll Pops stuck in their mouths - horizontally.

What's more, the murders turned out to happen for a reason that none of us will ever face. Monty Navarro learns after his mother's death that he's actually Monty D'Ysquith Navarro, the ninth in line for the Earldom of Highhurst. Ah! If he can only climb eight branches on the family tree, then he'll have enough wealth and position for Sibella Hallward, who's turned him down for being poor.

When Monty contacts one of the elite eight just to get to know the family, he gets an immediate brushoff. That makes an audience feel bad for him. The only way he's even going to get a glimpse of Highhurst Castle is to pay money to take a guided tour. When he does, he's made to feel inferior -and that makes us identify with him, too. After all, which of us hasn't had the feeling of not belonging when we've been in some hoity-toity place?

The authors were wise to have the first death be one of negligence with no malice aforethought. Monty's standing on a high tower with Reverend D'Ysquith (or #8, if you will) who's intoxicated. That the Reverend slips and is in danger of falling is his own fault.

That Monty does nothing to prevent it isn't.

That accident - which means one down, seven to go -- is enough to set off Monty.

Soon he's exacting as many murders as there are deadly sins. The authors were lucky to have Darko Tresnjak, whose Tony-winning direction kept matters light and frothy.

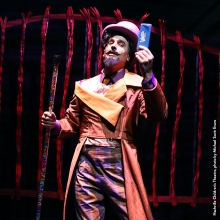

Another wise decision was to have one actor (Tony-nominee Jefferson Mays) play all the victims. Sure, economics was the reason, but by octet-ing, so to speak, the show lost another semblance of reality. And it did work in another context: members of the same family often resemble each other, don't they?

When you consider producing Gentleman's Guide at your high school theater, you may worry about finding the right performer who can handle eight roles (one, in fact, is in drag). But for high schools - and high schools only -- you aren't required to have one man play all. So you could have eight boys play the victims.

And if you have eight talented boys in your high school's drama club, congratulations!

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Monday at www.broadwayselect.com and Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com . He can be heard most weeks of the year on www.broadwayradio.com.