Filichia Features: Grounding The Little Mermaid, JR.

Filichia Features: Grounding The Little Mermaid, JR.

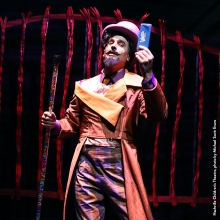

They fly through the air with the greatest of ease: those daring young actors currently appearing in the Paper Mill Playhouse production of The Little Mermaid.

Out in Millburn, New Jersey, plenty of performers have been hooked to wires and harnesses. They then zoom from the stage floor to the rafters and back down again. With an expansive light blue cyclorama behind them, the lovely illusion is created that sea creatures are swimming in their underwater world.

Director Glenn Casale’s vision may not help you much if you care to do Disney's The Little Mermaid JR. with your students. Perhaps you can’t have kids fly because you don’t have that much space above your stage. More to the point, you don’t dare because you don’t have the budget to have someone come in and fly kids, not to mention the insurance. You also don’t want to scare kids who think they’re ready to fly but once they’re high above the action find that they cannot.

While Casale’s superb production looks better than Francesca Zambello’s original 2008 version, you’re better off going with her solution: put performers on roller skates – that new-age kind that glide with little noise.

Of course you must discover in advance which of your kids can maneuver well on such devices. Don’t just take their word that they’re adept on skates. You saw that Funny Girl movie in which Fanny Brice claimed that she could skate -- and management soon learned that she could not. So don’t just audition for singers, dancers and actors; give your skaters a test-drive, too.

If your school has enough students to populate a school of fish, you might very well fill the stage with skaters who wouldn’t otherwise volunteer to be in a musical. Tell them you want them solely for their abilities on skates or skateboards; if, after a while, they seem at home on stage, ask if they’re willing to speak or even sing. Many will surprise you and say yes.

Having your kids wave their arms up and down will go a long way to suggest that they’re swimming. These include the performers who portray Ariel, the little mermaid – make that maturing mermaid; King Triton, her father who’s never stopped mourning the loss of his wife to carnivorous humans; Ursula, his sister who had a good deal to do with that murder; Flotsam and Jetsam, her two co-conspirators; Scuttle, the seagull who thinks he’s so smart (but we know better); Flounder, the fish who loves Ariel from afar; the Mersisters, Ariel’s six female siblings (each of whom sings beautifully) and last, but hardly least, Sebastian, the crab who’s entrusted by King Triton to keep both his eyes and claws over Ariel. His conundrum is that he loves her, too. What a hard time he has in keeping her from following her destiny into the human world of which she so wants to be a part.

One performer at Paper Mill is so convincing as an underwater creature that he should serve as inspiration to all. As Flounder, Christian Probst is always undulating, head slowly lurching forward first, shoulders next, belly last before reversing the process. He truly resembles the way so many fish look in water. While this may take some effort on the part of your actors – especially if they do it non-stop the way that Probst does – the effect will be well worth it.

Three boys won’t have to pretend to be underwater, for they’re humans: Prince Eric, the object of Ariel’s affection; Grimsby, his concerned regent; and Chef Louis, who reinforces King Triton’s worst fears that humans regard fish as meals and nothing more.

With Ariel, you must cast your student with the best voice to do justice to Alan Menken’s melodies. Much is made in Doug Wright’s script (as well as in Howard Ashman and Glenn Slater’s lyrics) that her voice is extraordinary. That it’s so glorious also results in the show’s great tragedy: Ariel so wants to become human that she trades her voice to Ursula for the privilege.

That brings us to legs. For the first part of the show, Ariel, along with her other peers, has none. Costume designer Tatiana Noginova smartly gives performers of both sexes floor-length, gown-like coverings with renderings of fish tails at the bottom. Ursula’s costumes, however, should have long tentacles attached. At Paper Mill, choreographer John MacInnis has Flotsam and Jetsam grab those long limbs and dance around her as if she’s a maypole.

Although the girl playing Ariel doesn’t have any singing to do in the second half of Disney's The Little Mermaid JR., she does have a new responsibility: she must be able to repeatedly fall on her face to suggest that she’s not used to these new-fangled legs that she’s acquired. Pick a sturdy lass.

Has any musical ever caused us to have such ambivalent feelings when a character ostensibly gets what she wants? On opening night, some of the Paper Mill audience applauded at the end of Act One when Ariel got her much-desired legs; others couldn’t, because they centered on the fact that she’d been robbed of her magnificent voice.

None of this negates the fact that there’s a beautiful story at work here, one that can profit both your students and their parents who are experiencing a generation gap. When Triton demands obedience “as long as you live under my reef,” tweens and teens will recognize the line even with the changed vowel sound.

To be fair, Triton has good reason to want his daughter to “stick to her own kind.” Humans, after all, were responsible for the death of his wife, thanks to their hooks and spears. Your Triton must show deep love for his youngest daughter and prove that he only wants what he perceives to be what’s best for her.

Whether he’s right is another matter. Ariel feels that one can’t blame all humans for a few wicked ones. The Little Mermaid reminds us the truism that there’s good and bad in every race, color and creed.

Thus, The Little Mermaid carries with it a Big Message for racial tolerance. In Fiddler On The Roof, Tevye asks Chava, “A bird may love a fish, but where would they build a home?” as a way of illustrating that Jews and Gentiles should not mix. But both are people; here, in The Little Mermaid, the question can be literally posed, for we’re dealing with two different species, one that cannot live in the sea and one that cannot live on land – unless a substantial change is made.

And yet, what’s wonderful is that at show’s end, both Ariel and King Triton admit where they’ve made mistakes and what changes in attitude each needed to make. Ariel feels bad that she caused her father so much worry from only thinking of herself; he realizes that the hardest part of love is letting go, and that he must show his love by doing just that. What musical could have as worthy a message -- that no one is always right and seldom is one always wrong? Make certain that your production has enough sincerity and that it doesn’t skate past it.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com.

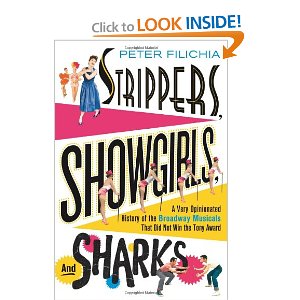

His book, Strippers, Showgirls, and Sharks – a Very Opinionated History of the Broadway Musicals That Did Not Win the Tony Award is now available at www.amazon.com.