Filichia Features: RAGTIME Without Wheels

Filichia Features: RAGTIME Without Wheels

If I had a nickel for every time a director has said to me "I'd love to do Ragtime , but I don't have a car," I could buy a premium seat to Hamilton.

All right, that's an exaggeration. Nevertheless, plenty who stage musicals have told me that the inability to get a convincing-looking Model T Ford on stage makes them choose another musical.

Yes, having a genuine car on stage is arresting and gets "ooohs!" from your audience. The fact that Coalhouse Walker, Jr. is successful enough to buy a snazzy new vehicle is vital to the plot where ignorant white bigots destroy it as a way of having "fun" and putting a black man "in his place."

Ragtime is set in 1906, so you can't just put your father's Oldsmobile on stage. You must have a Model T, which wouldn't be easy to find even if your great-grandfather were still alive.

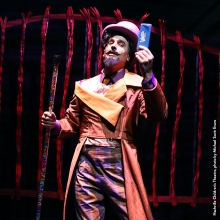

Staging whiz Curt Columbus wanted to do Ragtime , but as the artistic director of Trinity Rep in Providence, Rhode Island, he had to keep an eye on the budget, too. So, he decided to do the Terrence McNally-Stephen Flaherty-Lynn Ahrens musical without a car.

Heresy? Not if you have imagination, and Columbus has a dandy one. He made his 17 performers seem as if they'd just done a performance of another show, now arriving at their cast party in the green room, where there just happens to be a copy of E.L. Doctorow's novel.

Everyone starts reading the part that refers to him or her and suddenly we have a Mickey-and-Judy variation of let's-put-on-a-show, as the cast apparently once did Ragtime and now will nostalgically present it on the fly right then and there.

Two large pushed-together tables become the body of the car, and a pair of chairs atop it passes for its front seats. The tops of the tables also represent the deck of the ship on which the immigrants have traveled; all of them crawl out from under the tables to suggest that they've been in steerage. The way they squint tells us that they're seeing the light of day for the first time in a month or more. Later, a Ford assembly-line worker thrusts himself under the table and eases his body backwards to establish that he's been sucked into the machinery.

Later still comes the production's ugliest moment, which, unsurprisingly, involves car vandal ringleader Willie Conklin. He brings out an indelible ink pen, writes something on the table, which we then see when he upends it. The N-word. It stays there for the rest of Act One.

Staging the show as if actors are improvising saves money on costumes, too, for designer Kara Harmon puts everyone in contemporary clothes for most of the night.

Among the imaginative props are Evelyn Nesbit's fan - not made out of ostrich feathers, but pieces of old newspapers. Different interpretations include Emma Goldman's saying "I've been waiting for you," not to Younger Brother, but to a policeman she knows will now arrest her.

We get so caught up in what's happening that the show-within-a-show becomes simply a serious musical drama. Mother (the extraordinary Rachael Warren) finds an infant in her garden and the police arrive with Sarah, who abandoned it. When Mother says she'll take responsibility, the look on Mia Ellis' face is arresting, now that she sees she won't be arrested.

It's one of many reasons why an actress in your company will adore playing one of the strongest female roles in musical theater history. Without Father around, Mother gets the chance to find herself - and what she finds in her is worth its weight in platinum.

Columbus sets it on a not-so-large square, but set designer Eugene Lee (who's been with Trinity since the Johnson Administration) also offers a tall, four-level staircase. Having all 17 performers on it to represent the long wait at Ellis Island is most effective.

Also effective: Columbus' Coalhouse - Wilkie Ferguson III - can actually play piano. Audiences aren't fooled when the back of the baby grand is facing them and are painfully aware that the performer who sits behind at the keyboard isn't actually playing.

Ragtime satisfies in so many ways. Tateh makes the promise to his daughter that his fellow immigrants always made to their children: life will be better here. It turns out to be true, when they go from rags to ragtime to riches. If you're looking to use theater to spread messages of acceptance and diversity, this musical is a fine way to do so.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Monday at www.broadwayselect.com and Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com . His book, The Great Parade: Broadway's Astonishing, Never-To-Be Forgotten 1963-1964 Season is now available at www.amazon.com.