Filichia Features: What We Learned From 1776 Over the Years

Filichia Features: What We Learned From 1776 Over the Years

So how many times have I seen 1776, my friends keep asking me.

I recently passed the 46th anniversary of seeing this musical masterpiece for the first time. Since that heavenly Wednesday matinee in 1970, I’ve seen fifteen more productions.

Some have been better than others, of course. When I saw the original with William Daniels as John Adams – the man who would not be stopped from making America free from England – I stated that this was the finest performance I ever saw an actor give in a musical.

Looking back on it now, that wasn’t SO grand a compliment, because I’d be attending the theater for fewer than nine years, and hadn’t seen all that many shows on Broadway. For this native Bostonian, national tours that sometimes starred less than stellar performers and not-quite-together tryouts were the norm.

Today, I STILL say that Daniels’ performance is the best I’ve ever seen an actor give. That statement now carries more weight, given that I’ve now seen 80% of all Broadway musicals produced in the last 55 years.

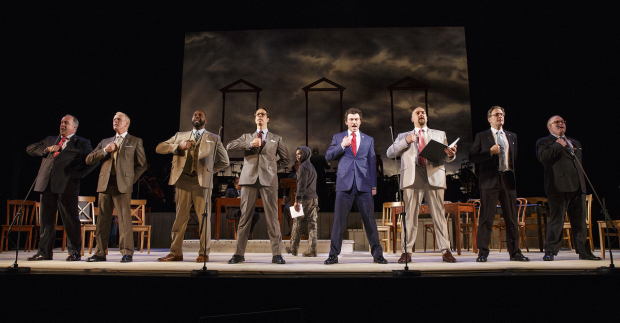

The cast of 1776 in New York City Center's Encores! Production (Photo by Joan Marcus).

So what have I learned from all sixteen productions? Certainly what’s been reiterated time and time again is that 1776 has the best-ever book for a Broadway musical. Peter Stone’s libretto was the main reason why the musical (that everyone initially thought would fail) won the Best Musical Tony – and in a year when Promises, Promises and even Hair were offering stiff competition.

That songwriter Sherman Edwards provided 1776 with a mere dozen songs didn’t hurt the show either, for here was an example of quality vs. quality. Musicians are notorious for reading paperbacks while waiting for their conductor to tap the podium and get them ready for the next song. Well, with no music for (literally) a half-hour between Songs Four and Five, each musician could read an entire novella in one sitting. Still, I wouldn’t be surprised if they put down the book to hear the conflict that is engaging– nay, mesmerizing – the audience sitting above.

How great a conflict? All 13 colonies must vote in favor of (or at worst abstain from) the independence issue. As it’s already June 7 (as a day-by-day calendar on the wall informs us) and only FIVE colonies of the 13 want to break free from England, the task seems impossible – especially with pesky Pennsylvania delegate John Dickinson not even willing to seriously consider the measure. To make matters worse, by June 29 only two more representatives have agreed to sign the Declaration of Independence. How will the other six colonies come around?

The dramatic irony, needless to say, is that we KNOW that the Declaration was signed on July 4. But how did the other six congressmen change their minds in a mere 125 or so hours?

See the show and find out. Better still, do it at your theater and make your audience proud and grateful that our Founding Fathers were able to compromise and bravely move forward to give us what became the greatest country in the history of the planet.

John Behlmann, John Larroquette, and Santino Fontana in 1776 at New York City Center's Encores! (Photo by Joan Marcus).

If you do a production, here’s some advice from a 1776 veteran of a sweet sixteen productions. In a show packed with “yeas” and “nays,” allow me to give mine (courteously).

The large day-by-day calendar and the Scoreboard of the States that tallies the “yeas” and “nays” on independence should be positioned next to each other center stage. Some directors like to frame the stage by having the calendar on extreme stage left and the scoreboard on extreme stage right. However, this choice doesn’t allow our eyes to simultaneously take in both. If they’re cozy-close to each other, our minds would be clicking away: “Wait a minute, that calendar says it’s already June 28 and – wow! – and four colonies are still dead-set against independence? How will they ever make it?!”

Each theatergoer needs the option of checking the score and the date when he needs to. The calendar and tally board are the reasons that the 1972 film doesn’t work as well as the stage version. Because the cinematographer only occasionally takes us to those score-keeping devices, we can’t easily retain how near or far the Declaration is from being ratified or what the deadline is; that eliminates a good deal of the clock-ticking suspense and the powerful drama.

(Too bad that the people who created the letterboxed DVD didn’t use that black space at the bottom to have a tally of “Yeas” and “Nays” as well as the date firmly imprinted in white. Then the film, with most of its excellent original cast, would have been the equal of the stage version.)

Have Congressional Custodian Charles McNair, who tends the scoreboard, pay rapt attention. I’ve seen productions where the actor playing this role tunes out, and when a delegate says “Yea” for independence, he’s erred and slid its colony into the “Nay” column – or vice versa. Make certain your McNair listens.

There’s more gravitas in Samuel Chase than first meets the eye. What first meets the eye, in fact, is this Maryland delegate’s weight. As is often the case with plays, films or TV series, the fat guy isn’t taken seriously simply because of the routine prejudice that heavy-set people endure. The hefty Ric Stoneback, who did the 1997 revival, chose to ignore that ignoble tradition. He roared his opinions with a seriousness of purpose, and became a genuine player in the action.

Should you use modern dress? I’ve seen it done that way more than once, and some of my friends have said they were glad they weren’t with me. Fred Abramowitz complained “Hey -- the show is called 1776, so the writers were pretty specific on when it was set. I’ll bet any company that does it in modern dress is just trying to save money on costumes.”

Josh Ellis, Broadway’s leading press agent until he retired, wrote “Even if the director opts for modern dress, John Adams’s lines about a do-nothing Congress makes me feel as if I’m watching CNN or MSNBC today. The modern business suits serve to drive that point home forcefully.”

Christiane Noll and Santino Fontana in 1776 at New York City Center's Encores! (Photo by Joan Marcus).

Rick Thompson, an actor, director and writer for many theaters in Maryland, stated “As for the argument that setting the show in the present reminds us that stubborn strife in Congress has lasted long beyond 1776 and continues today, I think we realize that on our own. Transplanting 1776 into 2016 destroys its inner reality. What’s next? South Pacific moved to present-day Iraq? My Fair Lady done with Klingons?”

And finally, to quote Frank Loesser (who was a fan of 1776 from the moment that Sherman Edwards brought it to him), “Here is the jackpot question in advance”:

Should you use non-traditional casting? Some directors have cast a few black actors as characters who were clearly WASPS in real life. Kevin Parcher wrote “Can I, a white man, be offended that a historical white character is being portrayed by a Black/Asian/Hispanic? For the record, I think it is fantastic. A director should pick whomever he or she feels will best fulfill his/her vision of the character and play.”

Walker Joyce, who once directed a phenomenally successful 1776 at his Bickford Theatre in Morristown, New Jersey, wrote “Non-traditional casting is a huge mistake for 1776. When race completely flies in the face of the text, it's nothing but a gimmicky distraction. As slavery is so key to Stone's perfect book, you simply can't have any black congressmen.”

With whom do you agree? If you work in an area unfamiliar with non-traditional casting, you might find this a barrier that many theatergoers can’t get past. On the other hand, if you believe in the practice, perhaps you can start the ball rolling in this direction. It’ll be a tough battle in many communities, but so was getting the United States of America off the ground.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Monday at www.broadwayselect.com, Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His book The Great Parade: Broadway’s Astonishing, Never-To-Be Forgotten 1963-1964 Season is now available at www.amazon.com.