Filichia Features: Remembering Canterbury Tales

Filichia Features: Remembering Canterbury Tales

March is about to turn into April – which will remind many of us the lines that we learned in high school, college or grad school:

“When April with his showers sweet with fruit the drought of March has pierced unto the root …”

Yes, they’re from Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales. It’s still considered one of the greatest works of literature, and one of the first important works written in English (albeit Middle English).

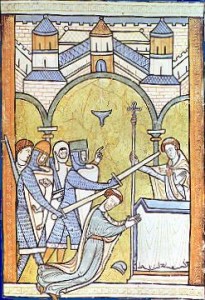

It has a most simple structure. Harry Bailey, owner of the Tabard Inn in Southwark, England, is taking a group of medieval pilgrims to Canterbury, where a shrine to martyr Archbishop Thomas Becket has been built. Because a long and boring journey looms, Bailey suggests that everyone tell a couple of stories on the way up and two more on the return trip. Whichever pilgrim tells the story that Bailey most likes will get a free meal at the Tabard at the end of the journey.

And yet, although millions know The Canterbury Tales, not enough people are aware that the work was the basis of a terrific musical, too.

To be sure, those who lived in England in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s know about the musical Canterbury Tales. Note that the article The was dropped, and that the words “The Musical” weren’t added. That practice wouldn’t be put into effect for decades.

Canterbury Tales opened in London on March 21, 1968 and ran for nearly five years: 2,080 performances in all. And this was this in an era when hitting 1,000 showings was an amazing achievement.

Actually, the musical endured quite a metamorphosis to reach the West End. Canterbury Tales was first a play in 1964, then a play with music in 1965, and then a concept album in 1966 that led to a stage musical. (And you thought that Jesus Christ Superstar had paved that route.) What’s more, despite the show’s being set in the long-ago, Canterbury Tales’ composers Richard Hill and John Hawkins used the pop-rock idiom for their songs – long before Andrew Lloyd Webber and Stephen Schwartz started trying it with their period pieces.

The Murder of Thomas Beckett

The 1969 Broadway production was admittedly not successful. A run of 121 performances was the best that it could do. There were no stars to speak of, but the marquee value would have been stronger 10 years later if the same performers had been cast. By then, Hermoine Baddeley, who’d played The Wife of Bath, was a regular on the hit series Maude; George Rose, who’d portrayed The Steward, had won a Tony for his Alfred P. Doolittle in My Fair Lady; Reid Shelton, who’d been The Knight, had become Annie’s Daddy Warbucks; Sandy Duncan, who’d been appropriately cast as a character called “The Sweetheart” in her Broadway debut, had had two TV series. Ah, timing, if not indeed everything, is still very important.

Needless to say, a two-hour musical can’t hope to encompass all 24 of Chaucer’s tales (26 if you count the two he didn’t get around to finish).

Bookwriters Martin Starkie and Nevill Coghill (the latter provided the lyrics) landed on five, but by the time the show reached Broadway, they’d whittled the number to four. Our storytellers were The Miller, The Steward, The Merchant and The Wife of Bath. All of them dealt with love and lust.

Anyone who well knows The Music Man has heard the name of Canterbury Tales’ creator. When River City’s First Lady Mrs. Eulalie Mackechnie Shinn wants to impress upon “Professor” Harold Hill just what a loose woman librarian Marian Paroo is, she and her friends say that the woman advocates “dirty books.” And who’s the first author whom the ladies choose to indict and offer as incontrovertible proof? “Chaucer!” one bellows.

To be frank, the lady has a point. Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales is, at the very least, ribald. The musical doesn’t shy away from at least one instance of dubious taste. It takes place in The Miller’s Tale, in which a would-be lover climbs a balcony to woo a fair lady, who tells him that if he closes his eyes, she’ll offer her face to kiss. What she instead offers is her bare gluteus maximus. If that’s not enough, the next night the ante is upped when that posterior is ready to go into action and expel gas.

That’s one reason why MTI frankly labels Canterbury Tales “Rated PG” and why there’s no Canterbury Tales, Jr. True, virtually every child with access to a television set has seen many a sitcom and film in which the breaking of wind has been subject for comedy. Canterbury Tales reminds us that there is indeed nothing new under the sun; seven centuries ago, Chaucer used this bodily function for a cheap laugh.

The Steward, who doesn’t like The Miller, decides to tell a story in which a miller’s wife cheats on him, although he does make her infidelity inadvertent. That spurs The Merchant to tell a tale about an errant wife who knows precisely what she’s doing when taking a lover and pulling quite a bit of wool over her much-older husband’s fast-dimming eyes. The Wife of Bath sends a knight on a very different type of quest; he must discover “What Do Women Want?” (In other words, Chaucer asked this question long before Sigmund Freud did.)

“What Do Women Want?” is one of the best songs in the show. The soft-rock ballad has amusing lyrics, thanks to the many different answers from the women whom the knight questions. But The Wife of Bath’s “Come On and Marry Me, Honey” is rollicking fun, too, and her “It Depends on What You’re At” is a 4/4 song that’s hardly four-square. “Where Are the Girls of Yesterday?” could be said to be the young musical grandson of Cole Porter’s “Where Is the Life That Late I Led?” And if you have an extraordinary soprano in your company, she’ll thank you forever for one of the most glorious unknown songs in the musical theater canon: “Love Will Conquer All.”

Words such as “love,” “girls” and “marry” may suggest that Canterbury Tales isn’t all that racy. And yet, there is that song in which a young man proudly describes his endowment. As a result, Canterbury Tales should be most considered by college, community and stock theaters – but it should be considered.

Do have a good brass section, though; the orchestrations that Hill and Coghill created go heavy on the horns. But what thrilling orchestrations they are. Canterbury Tales has a distinct sound; no other music sounds remotely like it.

Considering that Harry Bailey is willing to give a free supper to the pilgrim who tells the best tale, there’s a logical promotion you can offer if you present the show. Prior to the musical, station an interviewer and videographer in your theater’s lobby. As ticketholders enter the building, the interviewer with microphone in hand can ask, “And if you were making such a pilgrimage, what story would you tell in hopes of winning a free dinner?” The videographer captures the tale. Then, during the performance, a judge or two (or more) can play Harry Bailey and assess which story is the best. At the end of the show, the best storyteller is announced and the prize, like Harry’s, will be a free dinner, via a gift certificate. The ideal scenario has restaurateurs from all around your town signing up to be part of this promotion, with a different restaurant represented at every performance.

So take a look at Canterbury Tales for possible production. If you need a reason to produce it, be apprised that the 800th anniversary of Geoffrey Chaucer’s birth will occur in 2014. It’ll be here before you know it.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His newest book, Broadway Musical MVPs, 1960-2010: The Most Valuable Players of the Past 50 Seasons, is now available through Applause Books and at www.amazon.com.

You may e-mail Peter at pfilichia@aol.com. Check out his weekly column each Tuesday at www.masterworksbroadway.com and each Friday at www.kritzerland.com. His newest book, Broadway Musical MVPs, 1960-2010: The Most Valuable Players of the Past 50 Seasons, is now available through Applause Books and at www.amazon.com.

Share

Callboard

-

Shake and shimmy it with the #Hairspray20Challenge! Join MTI and Broadway Media in celebrating 20 years of #Hairspray. Duet this here or find us on TikTok! Special thanks to @broadwaymedia and @jammyprod. Choreography Guides are a licensor official resource that provides step-by-step instruction from Broadway and professional choreographers for your productions! Visit @broadwaymedia to learn more. #mtishows #youcantstopthebeat #hairspraymusical #goodmorningbaltimore

View on Instagram